From Implants to Editing: A New Era in Hearing Restoration

Key Findings

- Gene therapy provides outcomes comparable to cochlear implants in children with genetic deafness (OTOF mutations), supporting speech and sound detection while also improving hearing in noisy environments, sound localization, and music perception

- CRISPR-based gene editing shows promise for adults with DFNA41, a progressive form of genetic deafness, restoring hearing and balance in mouse models with a single injection and protecting against noise-induced damage

- The team is developing gene therapies for multiple mutations and age groups, advancing toward human clinical trials, and aiming to complement cochlear implants while restoring natural hearing

This article was written by Nicole Feldman and republished from the Fall 2025 Harvard Otolaryngology Magazine.

Subscribe to the latest updates from Otolaryngology Advances in Motion

An estimated 26 million people worldwide live with congenital hearing loss, up to 60 percent of which is caused by genetic factors. Cochlear implants have transformed the lives of more than a million people over the past six decades, but access remains limited, with fewer than one in 10 eligible patients receiving them. Outcomes also vary, with some patients gaining only modest benefits, and challenges such as music perception and speech recognition in noisy environments persist despite technological advances.

Gene therapy offers a new approach by addressing the underlying genetic causes of hearing loss. Zheng-Yi Chen, DPhil, Associate Professor of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery at Harvard Medical School and Principal Investigator and Ines and Fredrick Yeatts Chair in Otolaryngology at Mass Eye and Ear, has been at the forefront of this research. His team, in collaboration with colleagues at the Eye & ENT Hospital of Fudan University in Shanghai, first reported in The Lancet that adeno-associated virus (AAV)–based delivery of OTOF successfully restored hearing in children born with DFNB9, a severe form of autosomal recessive deafness.

Building on this milestone, the group later published in Nature Medicine the first trial to restore hearing in both ears of affected children. Treated patients not only regained auditory sensitivity but also demonstrated sound localization and improved speech recognition in noisy environments—capabilities that standard cochlear implants often struggle to deliver.

“At this time, the gene therapy trial is available only for individuals with OTOF variants, but my lab is actively developing approaches for other genetic forms of deafness, with promising results in mouse models,” Dr. Chen said. “One of the biggest questions from families has been how gene therapy compares with cochlear implants. Until recently, we had no evidence to guide those decisions.”

Figure 1

Zheng-Yi Chen, DPhil in his laboratory at Mass Eye and Ear.

Gene Therapy vs Cochlear Implants

To address the gap, Dr. Chen and his collaborators designed a study to directly compare outcomes among children who received gene therapy, those who received cochlear implants, and those who received both—gene therapy in one ear and a cochlear implant in the other. Participants ranged in age from one to 18 years and had severe to complete congenital hearing loss. To ensure a rigorous comparison, children were matched on duration of deafness, hearing thresholds and baseline speech ability before treatment. Of the 1,568 children screened, 72 were ultimately enrolled.

The study carefully aligned the groups so that children receiving gene therapy and cochlear implants were treated at similar ages, followed for the same periods and assessed for unilateral or bilateral interventions. This detailed matching allowed the team to attribute any differences in outcomes directly to the treatments themselves rather than external factors.

Results showed that gene therapy performed equivalently to cochlear implants in detecting sound and supporting speech recognition. “This was extremely reassuring, as it demonstrates that gene therapy can achieve the same level of effectiveness as the current standard of care,” Dr. Chen emphasized.

Beyond basic hearing, the study, published in JAMA Neurology, revealed distinct advantages of gene therapy in complex auditory tasks. Within six to 12 months, children who received gene therapy showed greater improvements in auditory and speech perception scores, faster auditory processing on electrophysiologic tests and better performance in challenging listening conditions, such as understanding speech in noisy environments. Music perception also showed notable improvement. While cochlear implants often limit pitch recognition and produce a mechanical auditory experience, children treated with gene therapy—and particularly those who received gene therapy in one ear and a cochlear implant in the other—showed significantly better accuracy in reproducing melodies and perceiving pitch. These results suggest that gene therapy more closely restores natural hearing.

Gene therapy also accelerated brain adaptation. Typically, cochlear implant recipients require one to two years of rehabilitation to develop fluent speech. However, gene therapy patients exhibited faster activation of brain regions associated with hearing and speech. Speech outcomes were evaluated through clinical assessments and electrophysiological measurements.

Dr. Chen noted that cochlear implants remain broadly effective across different types of hearing loss, while gene therapy is currently targeted to specific genetic mutations, such as those affecting the OTOF gene. The success of this targeted approach, however, demonstrates the potential for gene therapy to exceed conventional outcomes in patients with certain genetic hearing loss.

“Cochlear implants have transformed countless lives and remain exceptionally effective, but with the majority of congenital deafness rooted in genetics, these findings remind us that we must keep pushing forward to develop gene therapies that can restore hearing for all,” said Dr. Chen.

New Findings and Future Directions

While OTOF therapy targets children born deaf, Dr. Chen’s lab is also pursuing strategies for patients who lose hearing later in life. The team has expanded its focus to progressive, late-onset deafness caused by dominant mutations such as P2RX2, which leads to autosomal dominant deafness-41 (DFNA41). Unlike children with congenital deafness, these patients begin life with normal or near-normal hearing that gradually deteriorates. “We were excited to focus on these patients because their inner ear cells are still healthy when they are born, which makes them more likely to respond to treatment,” explained co-senior author Xue Zhong Liu, MD, PhD, Leonard M. Miller Professor of Otolaryngology at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. “This gives us a wider window for intervention, from childhood through adulthood.”

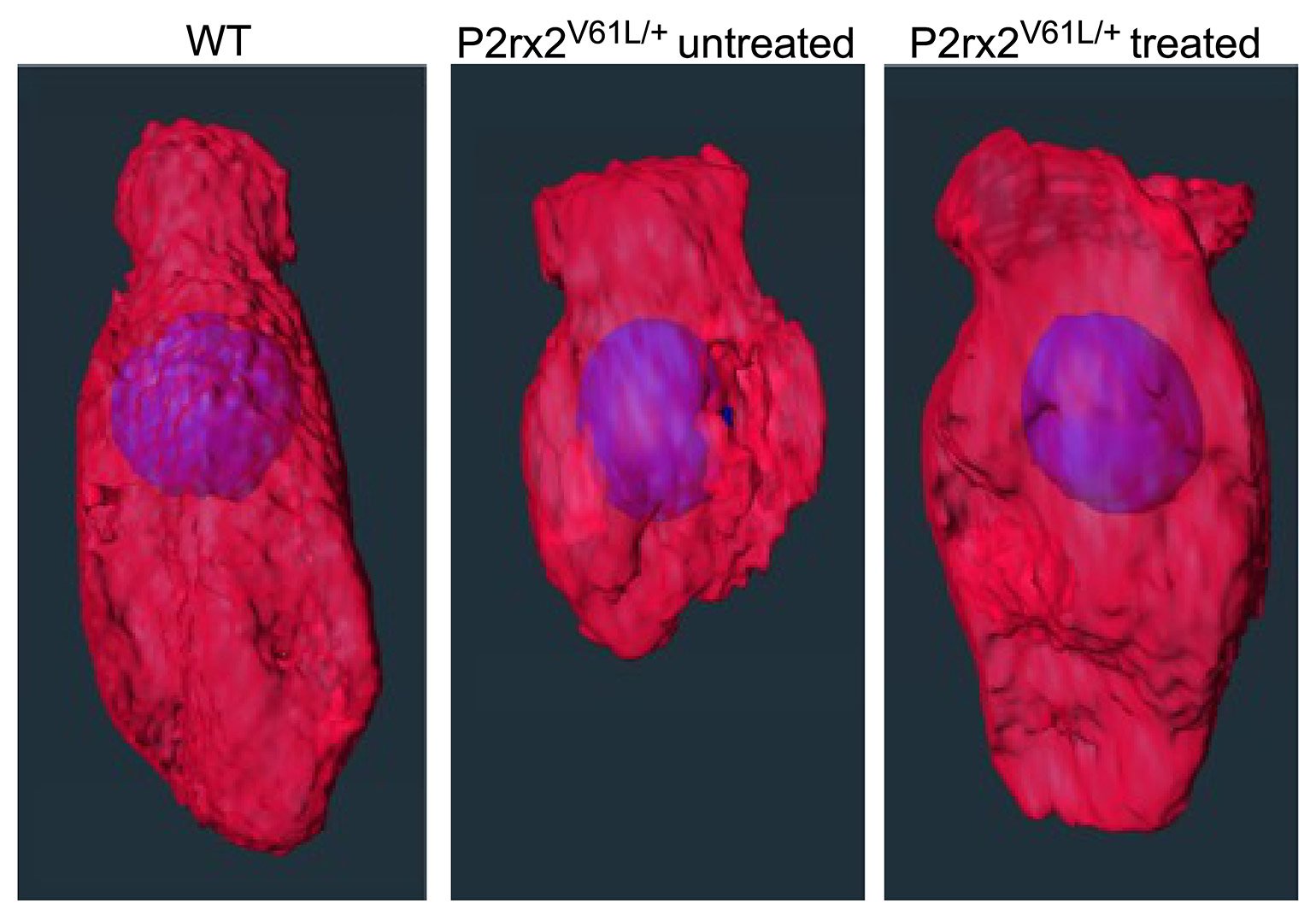

Figure 2

Editing treatment restored the morphology of the P2rx2 mutant inner hair cells. Three inner hair cells are shown: the wildtype (WT), untreated P2rx2 mutant and treated P2rx2 mutant.

In collaboration with multiple institutions, Dr. Chen’s team developed a one-time CRISPR-Cas9–based therapy delivered through an AAV2 vector directly into the inner ear of a mouse model. The therapy was designed to selectively disable the harmful mutation in the P2rx2 gene while leaving the healthy copy intact.

To accomplish this, the researchers designed a highly specific editing system (SaCas9 paired with a mutation-targeting guide RNA) and delivered it through a minimally invasive injection at the round window of the ear, a delivery approach already successfully used in humans. Genetic sequencing and tissue analysis confirmed that the therapy precisely removed the harmful mutation without introducing off-target effects or viral DNA integration.

The results, published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation (JCI), were groundbreaking. A single injection restored long-term hearing and balance in adult mice with DFNA41, offering proof that gene editing can rescue auditory function even in fully mature ears. Treated mice were also protected from hypersensitivity to loud noise, a known risk factor for patients with DFNA41, and early intervention produced even stronger benefits. The team further validated the strategy in human stem cells carrying the same P2RX2 mutation, underscoring its potential for clinical translation.

“Our study demonstrated how gene editing can be a one-time, lasting treatment for adults with genetic inner ear disorders, something previously thought to be possible only during early development,” Dr. Chen mentioned. Beyond restoring hearing, the dual benefit of protecting balance and protecting against noise-induced loss points to a therapy that could address multiple challenges faced by patients with progressive genetic deafness.

Looking ahead, Dr. Chen’s lab is advancing this work toward clinical application with support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Somatic Cell Genome Editing (SCGE) program. Investigational New Drug (IND)-enabling studies are underway to evaluate safety, biodistribution and toxicity in preparation for first-in-human trials. The NIH grant, under Dr. Chen’s leadership as principal investigator, supports parallel development of editing therapies for both DFNA41, caused by P2RX2 mutations, and autosomal dominant deafness-2A (DFNA2A), caused by KCNQ4 mutations. In partnership with the Mass General Brigham Gene and Cell Therapy Institute, the team is also building platforms and delivery systems designed to accelerate testing of new gene therapy strategies across a range of deafness-causing mutations.

By studying both congenital and late onset forms of deafness, Dr. Chen and his collaborators are building a framework for genetic therapies that span all ages. The ultimate goal, he emphasizes, is not to replace cochlear implants but to complement them and gather robust alternatives, restoring natural hearing for patients of all ages and genetic backgrounds.

Learn about the Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery