Dusting Vs. Basketing: Strategies for Disintegrating Renal Stones

In This Article

- Traditionally, a high-power, low-frequency holmium laser is used to fragment ureteral stones and kidney stones less than 2.0 cm in diameter, which are then extracted utilizing a basketing procedure

- Dusting, a new protocol for treating kidney stones using recent laser technologies, has proven to deliver successful patient outcomes equal to those of traditional basketing, according to a study by the Endourology Disease Group for Excellence (EDGE) Consortium

- The EDGE Consortium concluded that dusting provides equally successful outcomes but at a potentially lower cost and shorter surgical time than basketing

- Whether dusting or basketing is used depends upon how the stones fragment during the surgery

- Surgeon preference may be the guiding strategy, since the EDGE study confirms the similarity of the short-term reintervention rates and symptom-free rates after dusting and basketing

Ureteroscopic (URS) laser lithotripsy is one of the most common procedures for treating ureteral stones and kidney stones less than 2.0 cm in diameter. Traditionally, a high-power, low-frequency holmium laser has been utilized to fragment the stone into pieces, which are then extracted using a basketing procedure.

Subscribe to the latest updates from Urology Advances in Motion

However, researchers from the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Urology participated in a multi-institutional clinical study, published in The Journal of Urology, testing an alternative to basketing. The new protocol, called dusting, uses a new laser technologies—a holmium laser set to lower power but significantly higher frequency—which often results in ablation of stones into dust-like particles that pass naturally. According to the study performed by the Endourology Disease Group for Excellence (EDGE) Research Consortium, this approach provides equally successful outcomes but at a potentially lower cost and shorter surgical time. (Figure 1)

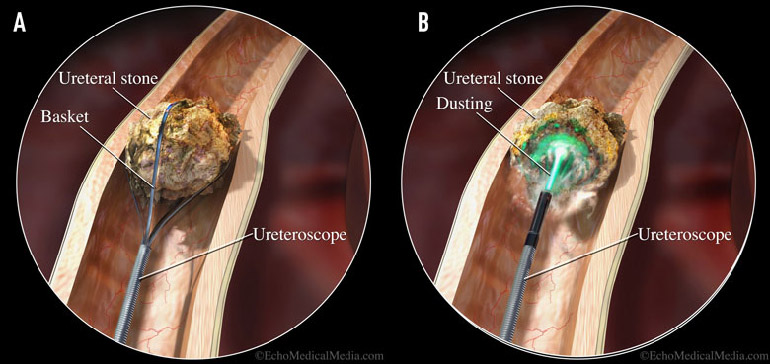

Figure 1: Dusting vs. Basketing

During the basketing procedure, a high-power, low-frequency laser fragments the stone, which is then removed with a basket retrieval device (a). In a new protocol called dusting, however, surgeons use low-power, high-frequency laser settings to ablate the stone into dustlike particles that pass naturally (b).

EDGE Trial Results

In the trial, 152 patients with renal stones were prospectively enrolled and followed for three months: 82 in the basketing group and 70 in the dusting group. Following URS laser lithotripsy, a complete stone-free rate of 86.3% was achieved in the basketing group compared with 59.2% in the dusting group.

However, there were no differences in hospital readmission rates, reintervention rates or other complications between the two groups, nor were there any significant differences in post-surgical symptoms from fragments.

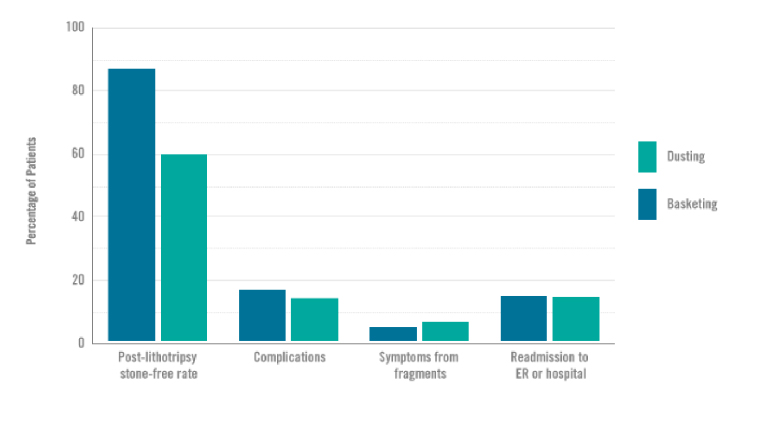

“This study shows that both protocols are very viable treatments,” says Brian Eisner, MD, co-director of the Kidney Stone Program at the Mass General Department of Urology and a co-investigator of the EDGE study (Figure 2).

Figure 2: EDGE Research Consortium study results

In the EDGE Research Consortium study of dusting vs. basketing during ureteroscopic lithotripsy, the basketing group achieved a higher stone-free rate. However, at three months, there were no major differences between the groups in terms of the rates of complications, symptoms from fragments, or readmission to the emergency room or hospital.

Which to Use?

The decision regarding which protocol to use is one that can be adjusted as the treatment progresses.

“A lot of it depends on how the stone fragments during the operation, which is something that is difficult to predict prior to the procedure,” says Dr. Eisner, who performs approximately 300 URS laser lithotripsy procedures annually, nearly half of the approximately 600 completed at the Mass General Department of Urology.

Dr. Eisner finds that, in general, kidney stones that have a lower Hounsfield density on preoperative CT scan are more amenable to dusting, as they are more easily pulverized into smaller pieces. Meanwhile, harder stones that break into larger pieces may be best treated via fracturing and basket extraction.

Dr. Eisner typically begins his operations with the dusting setting (low power, high frequency), observing the rate at which the stone fragments and the size of the pieces, aiming for residual particles of less than 1-2 mm. If the stone appears unlikely to fracture into dust-size particles using these settings, he switches to the fragmentation settings (high power, low frequency) on the same laser to complete the operation, and then basket-extracts the fragments at the end of the procedure. Additional equipment used for basket extraction of stone fragments, including baskets and ureteral access sheaths, however, may increase costs and procedural time.

“If you can get a stone treated quickly and effectively with dusting, limit the time a patient is in the operating room under general anesthesia, and potentially lower costs, that is an advantage for patients and the health care system in general,” Dr. Eisner says. “But every stone is not amenable to the dusting treatment. There are many ways to approach this procedure. My most common technique at this point is to start with dusting settings but convert to fragmentation and basketing if the dusting is not efficient.”

Another important aspect of this technique is for the surgeon to accurately evaluate the residual stone fragments and make sure that they have been made small enough to pass spontaneously. If they have not, then they need to be either fragmented with the laser into smaller pieces or basket extracted.

Ultimately, surgeon preference may be the guiding strategy, since the EDGE study confirms the similarity of the short-term reintervention rates and symptom-free rates after dusting and basketing. The EDGE Consortium is currently performing a longer-term follow-up of this initial study to track long-term rates of stone recurrence and determine whether symptomatic episodes will play a role in shaping future treatment programs.

About the Kidney Stone Program

Refer a patient to the Department of Urology