Pathways Case Record: Profound Weight Loss in a Patient With Polymyositis and Small Bowel Inflammation

In This Case Study

- A 39-year-old man presented with approximately 100 pounds of unintentional weight loss over six months. He experienced difficulties swallowing, right upper quadrant abdominal pain associated with feeling full after eating small amounts of food

- He underwent endoscopic procedures for his upper digestive system and colon, which revealed non-specific ileal mucosal inflammation. He was discharged with a diagnosis of presumed celiac disease

- He returned to the hospital three months later with proximal muscle weakness and continued weight loss. A thigh muscle biopsy showed inflammation in the connective tissue and muscle fiber, confirming an inflammatory myopathy

- Two years later, the patient presented with severe malnutrition and an estimated weight loss of 160 lbs over three years. Endoscopic procedures revealed remodeling of the small intestine and inflammation of the mucous membrane of the gastrointestinal tract

- The Pathways Consult Service at Massachusetts General Hospital was consulted and focused on the patient's concomitant skeletal and smooth muscle inflammation and gut dysmotility

A 39-year-old man with no significant past medical history presented with approximately 100 pounds of unintentional weight loss over six months. He experienced difficulties swallowing, right upper quadrant abdominal pain associated with feeling full after eating small amounts of food, and intermittent diarrhea. His weight at this initial presentation was 180 pounds, and labs were notable for positive gliadin IgA and HLA-DQ2, although his tissue transglutaminase IgA was negative. An extensive infectious workup, physical examination, and CT imaging were overall unremarkable. He underwent endoscopic procedures for his upper digestive system and colon, which revealed non-specific ileal mucosal inflammation. He was discharged with a diagnosis of presumed celiac disease.

Subscribe to the latest updates from Advances in Motion

He returned to the hospital three months later with proximal muscle weakness and continued weight loss. His workup was notable for a significantly elevated creatine kinase and positive aldolase and SSA-52 antibodies. An MRI of the bilateral femur, an electromyography study, and PET/CT scan were consistent with myositis, although no evidence of occult malignancy was seen. A thigh muscle biopsy showed inflammation in the connective tissue and muscle fiber, confirming an inflammatory myopathy. He was diagnosed with polymyositis (a disease resulting in muscle weakness on both sides of the body) and received intravenous immunoglobulin and prednisone, which was maintained as an outpatient.

No follow-up care occurred for approximately two years before the patient presented again for severe malnutrition. His weight was now 120 pounds, correlating to an estimated weight loss of 160 pounds over three years. MRI enterography showed active segmental inflammation of the distal ileum. Endoscopic procedures revealed remodeling of the small intestine and non-specific inflammation of the mucous membrane of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Video capture endoscopy was planned but aborted since a preliminary patency capsule took approximately one month to pass, suggesting extreme dysmotility. He was initiated on several promotility agents and appeared to have some functional improvement with the cholinesterase inhibitor pyridostigmine.

The Pathways Service in the Department of Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital was consulted and focused on the patient's concomitant skeletal and smooth muscle inflammation and gut dysmotility, driven by two questions:

- How are the inflammation in the small bowel and the skeletal muscle related?

- What is causing this patient's profound GI dysmotility?

Background and Diagnosis

The small bowel comprises three distinct layers: the mucosa, submucosa, and muscularis externa. The myenteric plexus within the muscularis externa controls smooth muscle contraction function. Traditional endoscopic biopsy samples the mucosa and portions of the submucosal layers and, thus, cannot effectively evaluate the muscularis externa or the enteric nervous system (ENS). Several electrical signals generated by the ENS are present in the GI tract. The primary signal types include: 1) slow waves, a basal electrical rhythm present at all times in a healthy ENS, and 2) spike potentials, which are present during food digestion and peristalsis. The expected gastric slow wave rhythm is three cycles per minute (CPM), or 0.05 Hz, and the expected small intestine slow wave frequency is 8-12 CPM (0.13 - 0.2 Hz). These signals can be used to assess the integrity of the ENS and determine whether clinical findings are due to muscular or ENS dysfunction. An electrogastrogram (EGG) is a non-invasive tool that utilizes cutaneous electrodes on the abdomen to record these ENS electrical signals, which could provide insight into our patient's presentation.

EGG tests are done with a food stimulus to observe the changes in the EGG waves before and after a meal. The EGG signals are evaluated based on the percent time in normal rhythm, bradygastria (slow wave frequency less than normal), and tachygastria (slow wave frequency greater than normal), as well as the amplitude change and frequency response after food is consumed. Exploratory research using EGG aims to understand different pathophysiology in gut motility disorders. A study examining adults with chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction identified that pathology consistent with visceral myopathy correlated with predominant brady-gastria and decreased amplitude after a meal (Dig Dis Sci). Pathology was consistent with underlying neuropathy correlated with predominant tachy-gastria and preserved response following eating. EGG could potentially be useful to gain an objective measure of the effect of gut motility agents on our patient.

Extensive crosstalk occurs between the ENS and intestinal immune cells, suggesting that enteric neuronal dysfunction could contribute to inflammation. The neurotransmitter acetylcholine plays an important anti-inflammatory effect in the small bowel, and acetylcholine receptor stimulation can decrease TNFα in the gut (J Physiol). Acetylcholine is also a key regulator of skeletal muscle at the neuromuscular junction and smooth muscle, promoting gut motility and involuntary constriction and relaxation of muscles. Given our patient's response to pyridostigmine, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor that increases acetylcholine concentration, it is reasonable to think that acetylcholine dysregulation could drive inflammation of both skeletal muscle and small bowel, including smooth muscle contributing to the patient's profound GI dysmotility.

Summary and Future Steps

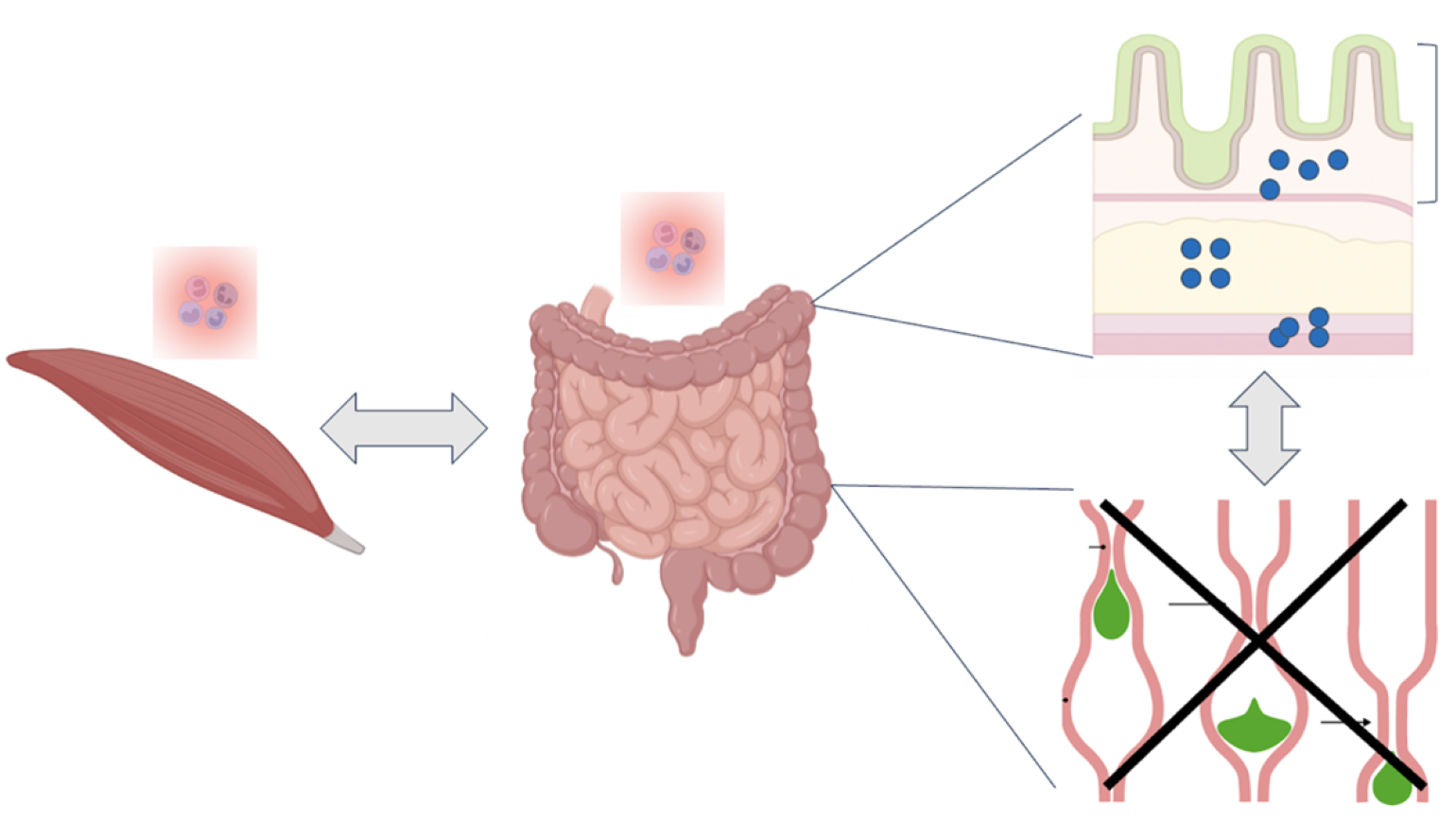

In summary, our patient, a man with three years of profound weight loss, was found to have inflammation of the skeletal muscle and the mucosal layer of the small bowel with severe GI dysmotility. Notably, a functional improvement was noted in response to pyridostigmine treatment. Here, we propose a series of assays to localize the lesion, determine the pathological cell type, investigate acetylcholine signaling in the gut, and test the role of various immune cell populations and cytokines on muscle contractions (Figure 1).

Figure 1

How do we explain inflammation of distinct tissue types in skeletal muscle and small bowel with the consequence of profound GI dysmotility? We propose several experimental techniques to identify neuronal vs. muscle dysregulation, characterize a pathologic cell type and identify a culprit antigen, and perform functional testing to evaluate response to treatment such as acetylcholine.

- To understand the cause of inflammation and dysmotility, we can utilize methods such as:

- We propose to obtain a full thickness biopsy of the patient's small bowel to visualize the submucosal and muscularis layers and thereby examine the structure and numbers of neurons and muscle fibrils in the gut. We would also stain for different neurons and localize different immune cell populations using immunohistochemistry. These studies could provide clues as to whether there is primarily a nerve or muscle issue causing dysmotility.

- Using an EGG, we could determine whether the issue is muscular or nervous system specific in the patient. A potential test could observe the difference before and after a meal by using EGG traces before and after a gut motility agent is given. This may provide insight into underlying pathophysiology and inform treatment decisions.

- We propose to perform flow cytometry immunophenotyping and single cell RNA-sequencing of the cells isolated from the patient's small bowel and skeletal muscle, which we will compare to healthy control tissue samples. This would provide information on whether there is a common pathological cell type between the gut and skeletal muscle. As previously demonstrated, network analysis of signaling pathways between various cell types could identify dysregulated and potentially targetable pathways in the patient (Cell). B cell receptor (BCR) and T cell receptor (TCR) signaling would additionally provide information on whether there is a clonal pathological process and identification of the antigens through either proteome microarray screening for BCR specificity or antigen prediction modeling for TCR specificity could provide clues as to whether the immune system is targeting a muscle or nerve antigen (Ann Oncol, STAR Protoc, J Proteome Res).

Lastly, we propose to utilize a recently published ex vivo gut culture system and titrate different amounts of acetylcholine into the culture medium to examine the peristalsis dose response curve for the patient compared to healthy tissue (Biomolecule, Cell). Functional studies testing the effect of immune cell and cytokine depletion and addition on peristalsis in this gut culture system will allow for identification of immune cell populations or cytokines that may be playing a particular pathogenic role in the patient's dysmotility.

Learn about the Pathways Consult Service

Refer a patient to the Pathways Consult Service