Police Killings of Unarmed Black Americans Harm the Mental Health of Other Black Americans

Key findings

- Among black Americans, exposure to one or more police killings of an unarmed black person in the same state in the previous three months was associated with an increased number of poor mental health days (0.35-day increase per person, per month)

- At the population level, the relative increase in poor mental health days was 8.7%

- Police killings of unarmed black people had no effect on the mental health of white Americans

- Across the entire population of black American adults, police killings of unarmed black people are estimated to cause 55 million excess poor mental health days per year

Black Americans are nearly three times more likely than white Americans to be killed by police, and five times more likely to be killed while unarmed. Small studies have suggested that beyond the consequences for the victim and their family, police killings also damage the mental health of people who are not directly connected to the victim.

Subscribe to the latest updates from Neuroscience Advances in Motion

Now, using nationwide data, a research team led by Alexander C. Tsai, MD, PhD, a researcher and associate director for trainee development in the Chester M. Pierce Division of Global Psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, has found for the first time that police killings of unarmed black Americans harm the mental health of black adults who live in the same state as the victims. Their report appears in The Lancet.

Dr. Tsai's team combined two sources of data. For information on the mental health of Americans, they consulted the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), a database that stores the results of annual, nationwide telephone-based surveys of U.S. adults. 103,710 black Americans were interviewed for the BRFSS from 2013 to 2015. One of the questions asked in the BRFSS is, "Now thinking about your mental health, which includes stress, depression and problems with emotions, for how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health not good?"

The researchers also delved into the Mapping Police Violence (MPV) database, which addresses concerns about underreporting in government statistics by drawing from several media and crowd-sourced databases, then cross-checking suspected police killings against police records, social media and obituaries.

Using MPV data for 2013–2016, the researchers calculated that 49% of the black survey respondents were interviewed within three months after at least one police killing of an unarmed black American in their state. On average, respondents were exposed to one such killing during a given three-month period.

Black respondents reported an average of 4.1 days of poor mental health during the month prior to their interview. Compared to that, exposure to one or more police killings in the same state was associated with a 0.35-day per month increase in poor mental health, which is an increase of 8.7% in poor mental health days.

For each police killing in the previous three months, the number of poor mental health days increased by 0.14 days per month, a relative increase of 3.3%.

Age, sex, income and years of education had no influence on the results.

However, the researchers point out that these findings may actually be underestimated. Many of the relevant killings during the study period received nationwide media coverage. They may, therefore, have had spillover effects on the mental health of black Americans living in other states who were not studied.

Also, the MPV database may not have captured every relevant killing, and race was unknown for 7% of unarmed victims in the MPV.

Even so, based on their data, the researchers estimate that police killing of unarmed black people contributes 1.7 extra poor mental health days per black American per year. That represents 55 million excess poor mental health days per year for the overall U.S. black population.

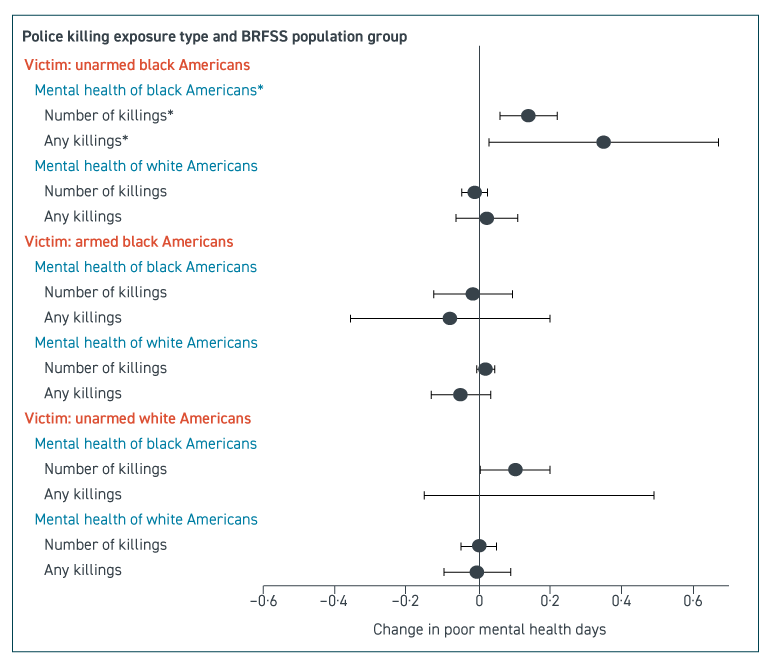

In contrast, killings of unarmed people by police had no mental health effects on white Americans surveyed for the BRFSS, whether the victim was black or white (Figure 1). Police killings of armed black Americans did not affect the mental health of either black or white respondents.

Fig. 1: Changes in poor mental health days associated with exposure to police killings

Data is broken out by race of police killing victim, whether the victim was armed and race of the BRFSS respondent. Each estimate in this figure is derived from a separate regression. BRFSS=Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. *Primary analysis.

Other researchers have proposed a number of explanations for why police killings of unarmed black Americans harm the mental health of black people in general:

- Increased fear of victimization and death

- Heightened awareness of structural racism and lack of fairness

- Feelings of anger, vulnerability, lower social status or lower self-worth

- Increased vigilance

- Diminished trust in social institutions

- Activation of prior trauma

- Identification with the deceased

- The experience of communal bereavement

Future research should investigate the relative importance of these factors, the authors urge. They also call for research into whether other forms of structural racism, such as mass incarceration, contributes to poor population mental health. There is also a need to examine how police killings affect other populations, including Latinos, Native Americans and police officers themselves.

But there is sufficient evidence now, the researchers say, that police violence in general should be considered a public health issue.

Interventions are needed to reduce the prevalence of police killings and to support affected communities when police killings do occur, the research group recommends. Those interventions might best be applied as part of a broader reform of the criminal justice system.

view original journal article Subscription may be required

Learn more about the Chester M. Pierce Division of Global Psychiatry